Dr Stuart Parkinson and Andrew Simms summarise SGR’s new research on the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of the global football sector, and explore whether reducing the carbon footprint of football can help accelerate wider climate action.

Responsible Science blog; publication: 3 February 2025

Football is the world’s most popular sport and has an enormous cultural reach. Annual attendance at matches played in the world’s top domestic leagues is around 220 million, and it’s been estimated that about 5 billion people – about 60% of the world’s population – ‘engaged’ with the last men’s World Cup Finals tournament in 2022.

But the sport now faces a huge threat from climate breakdown. Los Angeles is set to host multiple games at the 2026 FIFA men’s World Cup - and was recently was scorched by record wildfires. Players' health is threatened by the likelihood of extreme heat at 14 out of 16 of the World Cup venues.

Yet football’s own role in fuelling the climate crisis is largely overlooked. Estimates of the global carbon footprint of the sport have been virtually non-existent – until now. Even more disturbing is that efforts to reduce football-related emissions have barely started.

Football’s carbon footprint

In a new study by Scientists for Global Responsibility and the New Weather Institute, we estimated that the carbon footprint of football is approximately 64-66 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). This is similar to annual GHG emissions of the whole nation of Austria. Included within this total are emissions due to a wide range of activities, including stadium energy use, construction and renovation, merchandise, fan and team travel to matches, and, unusually, sponsorship deals with high carbon corporations.

Our estimate concluded that, by far, the largest source of emissions was due to the sponsorship deals – indeed, this represented about 75% of the total.

High carbon corporations use sponsorship deals with sport and other cultural activities to promote their brand and, crucially, increase sales of their polluting products. This commercial activity was pioneered by the tobacco industry which, for decades, used sport as a billboard to promote its lethal products. The exact relationship between the funding provided through sponsorship and the GHG emissions which result from the increased sales is difficult to determine, given the commercial secrecy around the deals themselves and complex workings of the economy. However, a group of European researchers with whom we work have produced a new methodology for estimating these emissions based on corporate economic behaviour. Using this, we have for the first time been able to include a category of ‘sponsored emissions’ in our totals.

The role of high carbon sponsorship

In many ways, the prominence of sponsored emissions is not surprising. In recent years, elite football teams – and, crucially, its governing bodies – have been ramping up lucrative sponsorship deals with high carbon sectors, including oil and gas corporations, airlines, car manufacturers, and fast food chains. Most disturbingly, the global governing body FIFA has recently negotiated a deal with Aramco, the world’s largest oil and gas company, based in Saudi Arabia. This deal includes top billing at the next men’s World Cup Finals in North America in 2026. And the hosting of the 2034 World Cup Finals has just been awarded to – you guessed it – Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, the English Football Association is sponsored by Emirates, an airline based in the United Arab Emirates. This deal includes the men’s FA Cup, the world’s oldest national football competition. Then there’s the current champions of the English Premier League, Manchester City – they are sponsored by Etihad, another Middle-Eastern airline. Looking further afield within Europe, we see that the current European champions, Real Madrid, are also sponsored by Emirates. The largest club sponsorship deal we were able to identify from our research was Paris St Germain’s hook-up with Qatar Airways, worth about $80 million per year. Suitably bank-rolled, Paris St Germain are current French champions.

All this high carbon finance pouring into football is helping to further normalise behaviours and lifestyles which are destabilising the climate system, threatening our society and natural ecosystems. Efforts to curb air travel, gas-guzzling SUVs, consumption of animal products, and numerous other high pollution activities are being undermined by this ‘colonisation’ of the cultural space.

Air travel and other GHG emissions

Our new study also looked at the other main sources of GHG emissions within football. This data was drawn from a range of sources including sustainability reports of football clubs and governing bodies (where they exist!), academic papers, and other research reports. Although there were large data gaps, and much that did exist was of poor quality, we were able to discover that two other sources of emissions are particularly important: fan travel to matches, especially by car and plane; and new stadium construction, especially for major tournaments.

We estimated that the average match in a men’s domestic elite league – such as the English Premier League – led to about 1,700 tCO2e. About half of this was due to fan travel, mainly by car. For an international club match – for example, in the UEFA Champions League – this rises by about 50% due to air travel by visiting ‘away’ fans, and even more if it’s a semi-final or final. One match at the men’s World Cup Finals, we estimated causes between 44,000 tCO2e and 72,000 tCO2e – between 26 times and 42 times that for a domestic elite game. The emissions of the World Cup match is equivalent to between 31,500 and 51,500 average UK cars driven for a whole year.

A critical factor in these calculations is how to allocate the emissions related to building new stadiums for the tournament. Some GHG emissions accounting methodologies allow for a very large proportion of these emissions to be allocated to future (post-World Cup) matches played at these stadiums, but many of these new venues are under-used, as the demand for 40,000-seater stadiums (the minimum size for stipulated for World Cup Finals matches) is rarely required in most nations. Hence, we argue that most of the emissions should be allocated to the World Cup itself, and hence the emissions per match should be towards the higher end of the range above.

Of the non-sponsored emissions, we estimated that over 93% of them were caused by elite football – either at a national or club level – demonstrating that it is at this level that climate action needs to be focused.

Reducing emissions

Clearly, according to our analysis, the top focus for climate action in the football sector should be on a rapid phaseout of sponsorship deals with fossil fuel corporations, airlines, and other highly polluting companies. This would help at a critical time when a move to low carbon behaviours offers one of the fastest options for reducing emissions in wider society.

Indeed, given the way in which these lucrative sponsorship deals have come to dominate the top clubs and tournaments in the world, there would arguably be a benefit in terms of the competitiveness of the sport. No longer would it be so easy to predict the winners of the elite leagues and cups.

The next priority is to reduce the number of international matches played in order to reduce air travel. Again, the elite level is key. The men’s UEFA Champions League has this season increased the number of matches in the competition from 125 to 189 – an increase of more than 50%. Meanwhile the next men’s World Cup Finals is scheduled to include 104 matches – up from 64 in 2022. To make matters worse, the tournament is being played across Canada, the USA, and Mexico – the widest geographical area ever used for the competition. These increases in the numbers of matches need to be reversed (at minimum) – and the focus of international matches needs to be on encouraging local fans to attend, not those from thousands of kilometres away.

Again, there would be benefits for the sport in pursuing these changes. Professional footballers are increasingly being pressured to play more and more matches per season, leading to burnout. Reducing the numbers of international matches would improve their welfare.

Some clubs and governing bodies have signed up to UN Sports for Climate Action Framework, which includes targets to half emissions by 2030 and reach ‘net zero’ by 2040. However, through the use of loopholes such as carbon offsets, organisations can avoid significant near-term action.

Some hopeful signs

There are some initiatives that are starting to turn the tide on the reckless behaviour of the elite football industry. For example, a group of over 100 leading women footballers has called for an end to Aramco’s sponsorship deal with FIFA, while top German club Bayern Munich dropped Qatar Airways as a shirt sponsor following fan protests over human rights concerns. Some clubs like England’s Forest Green Rovers are pioneering low-carbon action. Also, measures to improve surface public transport and increase its usage by fans have become a feature of some football tournaments such as World Cup Finals and the EUROs. Meanwhile, initiatives such as Pledgeball and Planet League are having some success encouraging football fans to adopt low carbon behaviours through club-based competitions, while other groups like the Cool Down Network are making the climate issue a permanent feature of commentary on the game.

However, we urgently need more ambition, both to protect society and the sport itself. Given the cultural reach of football, strong action in this sector could change the global conversation on climate issues, and help to stem the rising tide of climate disasters like the one in Los Angeles.

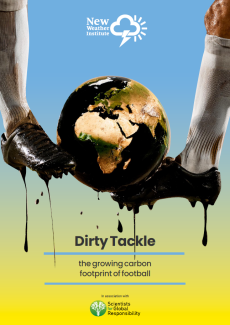

Dr Stuart Parkinson is Executive Director of Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR), and holds a PhD in climate science. He is lead author of the report, Dirty Tackle: the growing carbon footprint of football.

Andrew Simms is Assistant Director of SGR, Co-director of the New Weather Institute, Co-founder of the Badvertising campaign, and Coordinator of the Rapid Transition Alliance. He is co-author of the Dirty Tackle report.

This article is an expanded version of one published in The Ecologist.

Image credit: New Weather Institute