Dr Ian Campbell shows how, on current trends, Britain’s carbon emissions will exceed its fair share of the limit necessary to hit the 1.5°C Paris target within two years. He outlines the key implications for policy-makers and society as a whole.

Responsible Science blog, 5 August 2024

NB An updated version of this article was published in July 2025 and can be found here.

There is much agreement that CO2 emissions must be markedly reduced in order to limit climate change, but less agreement on how fast this must be done, with the UK government having a Net Zero 2050 policy [1], and others advocating a 2040 [2] or 2030 [3] limit.

Proper planning requires policies to be based on robust scientific evidence. This article summarises the science of carbon budgets and the choices that the UK has concerning the speed of its emission cuts.

The science of carbon budgets

Most of the CO2 released from burning fossil fuels and deforestation remains in the atmosphere for centuries or millennia, so the concentration of CO2 steadily rises. As the atmospheric CO2 rises, the average global temperature rises. From the amount of CO2 emitted in the past, and the effect that it has had, we can estimate how much more CO2 can be emitted if global heating is to be kept below a particular limit such as 1.5°C. This is known as the CO2 budget, or carbon budget.

In the Paris Agreement of 2015 [4], countries committed to restrict global temperature change to well under 2°C, and pursue efforts to keep it below 1.5°C. This translates to limiting further global CO2 emissions to the appropriate carbon budget. Greenhouse gases other than CO2 are of much less importance in the long term because of either their relatively short persistence in the atmosphere or their low proportion of overall emissions. Regarding division of the global carbon budget between countries, the Paris Agreement specifies that developing countries can increase emissions for a period to facilitate economic development and poverty alleviation, while developed countries must reduce emissions immediately (i.e. faster than the global total), and specifies equity between nations, which is usually interpreted as an equal share for each person of the global carbon budget.

The scientific consensus is that global heating can be limited to 1.5°C if total global emissions since the start of 2020 are limited to 400 billion tonnes CO2 [5] (this is with 67% confidence). This is approximately 50 tonnes per person on the planet. This is a lifetime limit, which will run out in a country with average emissions in 2030.

The UK’s fair carbon budget for 1.5°C

The UK's CO2 emissions are currently around 8 tonnes per person per year [6][7], so the UK has already used around 32 tonnes of its per capita budget of 50 tonnes in the 4 years to the end of 2023. This leaves a residual budget from the start of 2024 of 18 tonnes CO2 per person. If emissions continue with little change, this will run out in just over 2 years from the start of 2024, i.e. in early 2026, much sooner than generally discussed.

Below are a number of pathways for emission reduction which illustrate the choices in the UK. The carbon budget charts have been generated by the calculator at the Carbon Independent website [8], and can be replicated there via a user interface. Similar calculations and conclusions have been published in academic reports [9][10][11] – demonstrating that many in the climate science community already understand and accept the validity of this sort of analysis.

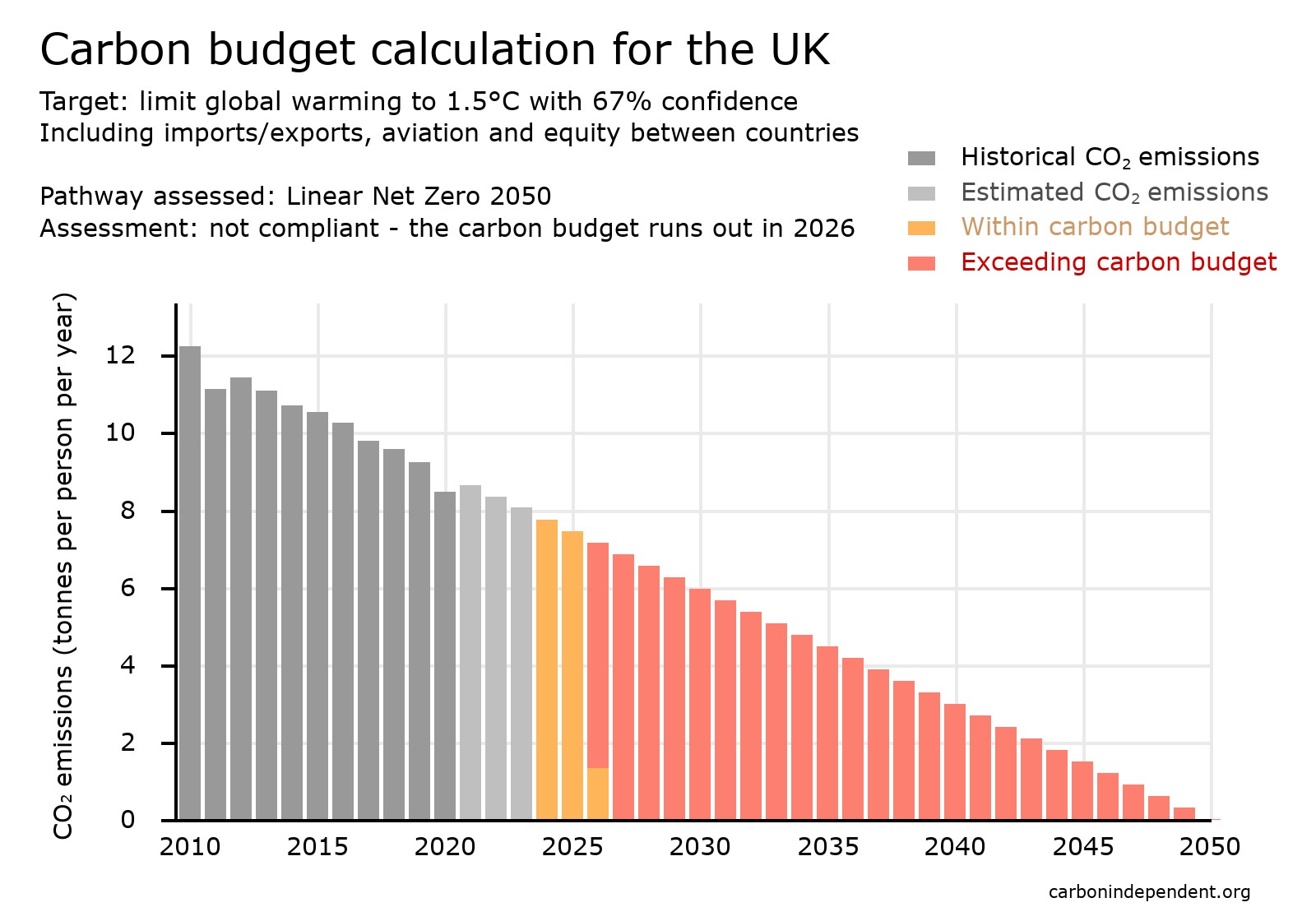

1. Net Zero 2050 (linear decline): not compliant with the carbon budget

A pathway often discussed is ‘Net Zero 2050’, where net CO2 emissions are reduced to zero in 2050.

A pathway often discussed is ‘Net Zero 2050’, where net CO2 emissions are reduced to zero in 2050.

One version of this is to cut emissions steadily, by the same amount each year, which gives a sloping straight line on a chart of annual emissions. This can be termed ‘linear decline’. The carbon budget runs out in 2026, and so the pathway is not compliant with the residual carbon budget. In fact, it would emit three times as much CO2 as the carbon budget of 50 tonnes per person [9][12].

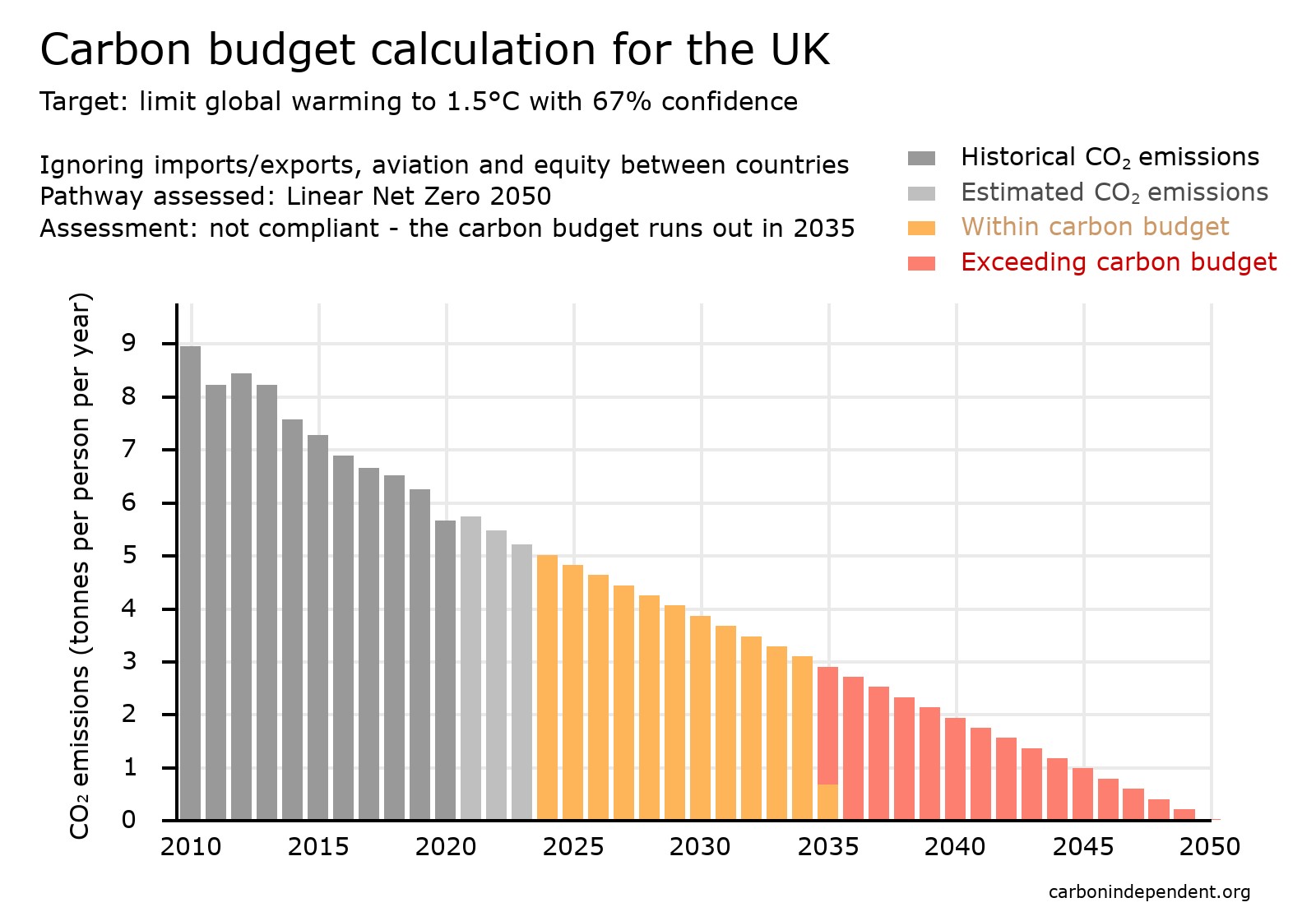

2. Net Zero 2050 (linear decline) ignoring imports/exports, aviation and equity between nations

Some published carbon budget calculations ignore emissions generated in imports/exports and also ignore aviation emissions and the Paris commitment to equity between nations. By taking more than its fair share of the global budget and ignoring some of its emissions, the UK’s budget lasts until 2035 (see chart), and by accepting a lower level of certainty of meeting the 1.5°C target, the budget lasts until 2050.

Some published carbon budget calculations ignore emissions generated in imports/exports and also ignore aviation emissions and the Paris commitment to equity between nations. By taking more than its fair share of the global budget and ignoring some of its emissions, the UK’s budget lasts until 2035 (see chart), and by accepting a lower level of certainty of meeting the 1.5°C target, the budget lasts until 2050.

This is essentially the UK government’s approach.

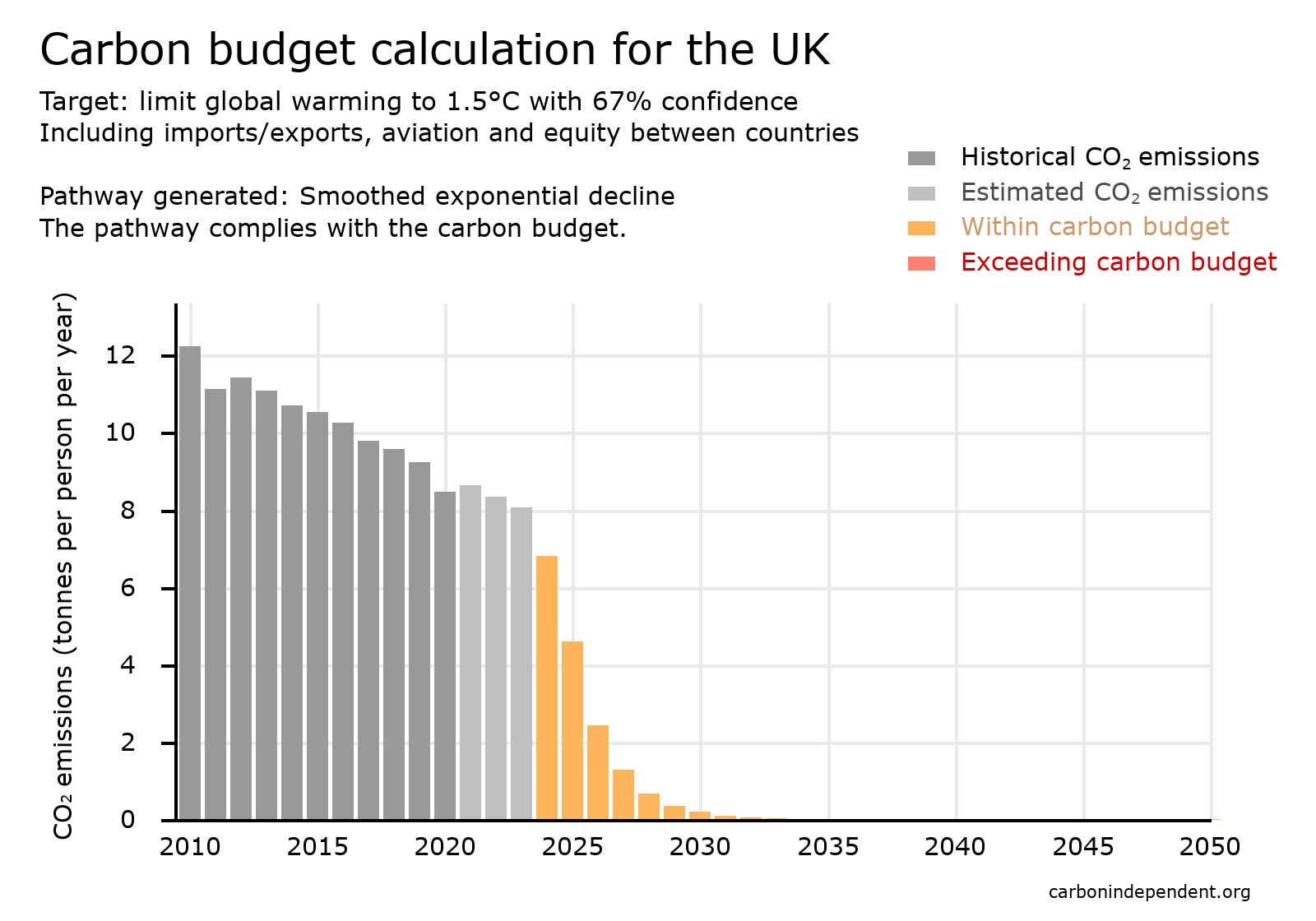

3. Compliant smoothed exponential decline for 1.5°C

The third chart shows how fast emissions need to be reduced in order to comply with a fair UK carbon budget. Cuts must be over 90% by 2030.

The third chart shows how fast emissions need to be reduced in order to comply with a fair UK carbon budget. Cuts must be over 90% by 2030.

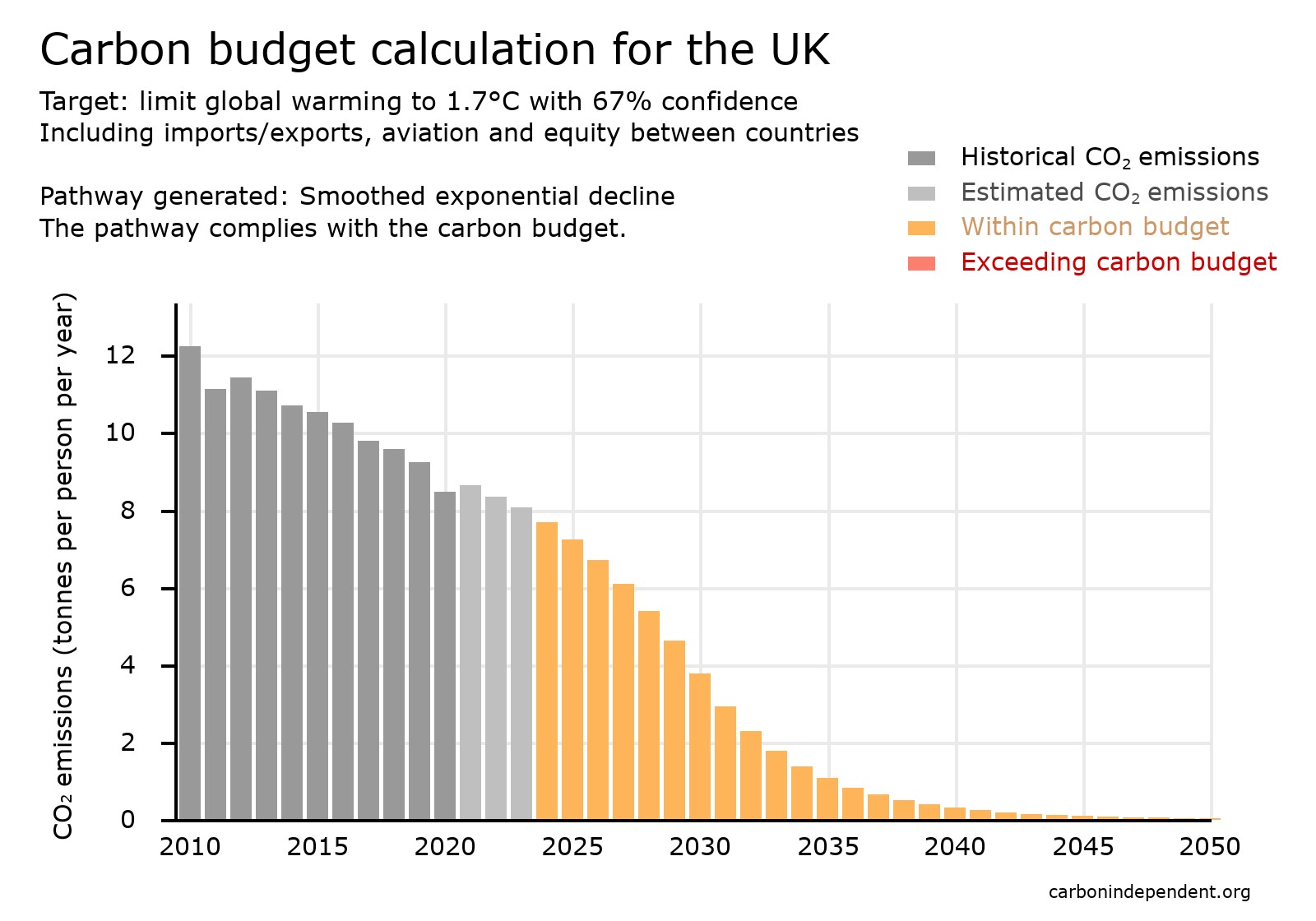

4. Compliant smoothed exponential decline for 1.7°C

With the lack of honest accounting and proper discussion, we must consider scenarios where the 1.5°C fair budget is exceeded.

With the lack of honest accounting and proper discussion, we must consider scenarios where the 1.5°C fair budget is exceeded.

This chart shows a pathway compliant with a 1.7°C fair UK carbon budget (an exponential decline with initial smoothing).

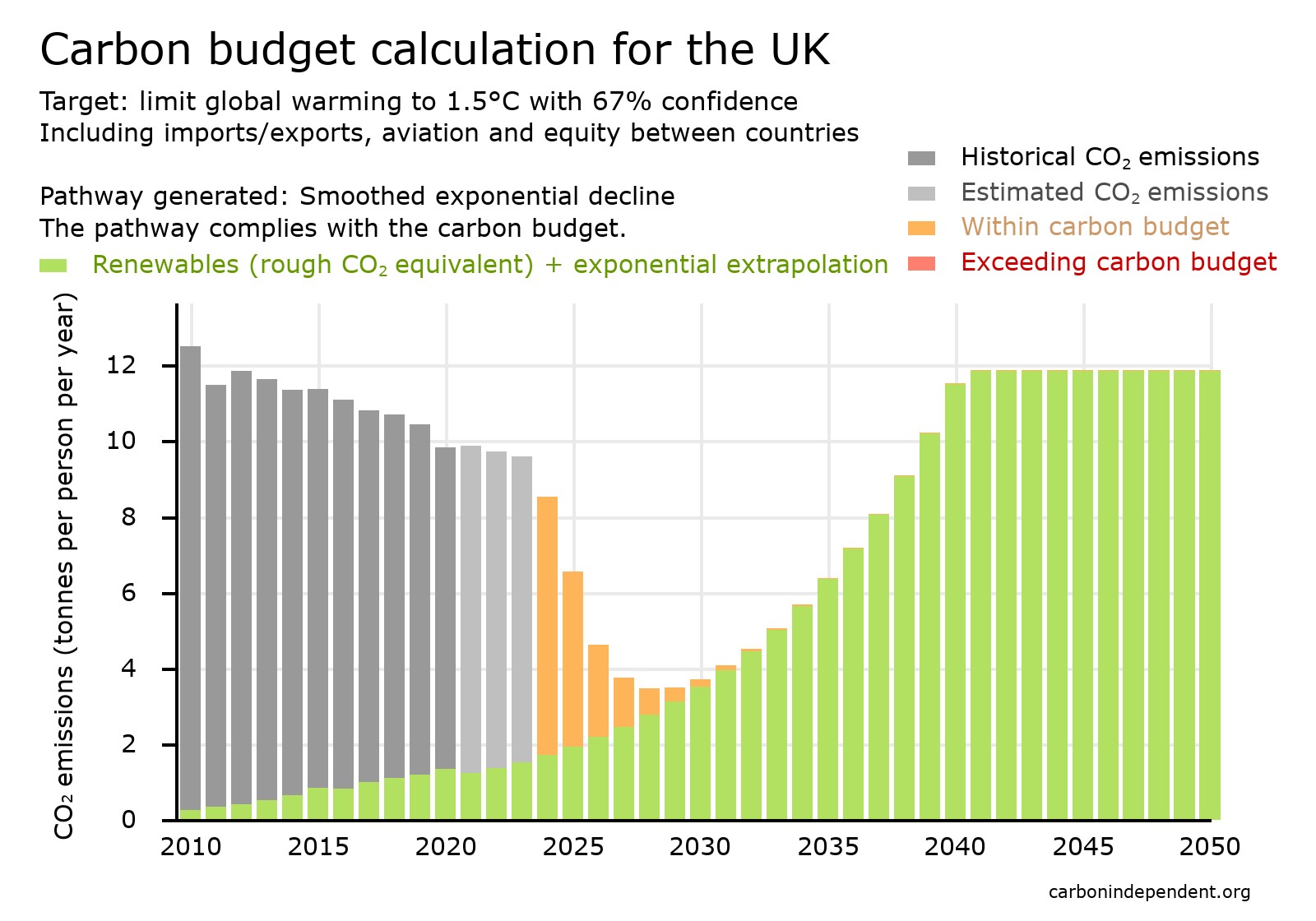

5. Compliant smoothed exponential decline for 1.5°C with renewable energy

UK renewable energy use has increased by 81% in the last 5 years [13], which equals a 13% compound annual increase.

UK renewable energy use has increased by 81% in the last 5 years [13], which equals a 13% compound annual increase.

The final chart shows this UK renewable energy use as a ‘CO2 equivalent’, together with extrapolation on the basis that this 13% annual growth continues.

Clearly, rapid phasing out of fossil fuels means a radical reduction in total energy use, but this need only be temporary.

Conclusions

The conclusions from the calculations are as follows.

- The UK’s fair carbon budget for limiting global warming to 1.5°C will run out in 2 years at current emission levels.

- The UK's current Net Zero 2050 timescale of emission cuts is grossly inadequate – it is derived by ignoring the commitment to equity between nations, ignoring emissions generated in the manufacture of imports, and ignoring aviation.

- If the UK wants to keep its promises under the Paris Agreement, urgent radical reduction in fossil fuel use is necessary, i.e. over 90% by 2030.

- While these conclusions are based on the scientific consensus, they are not widely understood, let alone discussed.

- Given the very limited timescale, technologies with long lead times for deployment such as carbon capture and storage are not viable solutions. The main focus needs to be on rapid expansion of existing renewable energy technologies (such as wind and solar), energy efficiency measures, and behaviour change. Strong action to curb fossil fuel extraction is also essential.

- Political and industrial decision-making on climate change has failed, and needs major reform.

- In order to make good decisions on climate change, there must be an honest debate based on robust scientific evidence, and an understanding of the immense harm being done to people and planet by the current lifestyles of the world’s wealthier groups.

Ian Campbell BA BSc MD FRCS FRCR has worked as a doctor and as a medical statistics consultant. As well as medical qualifications, he has a degree in statistics and a doctorate in the use of statistical methods in cancer research. His research on climate statistics is published on the Carbon Independent website [8].

References

1 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6194dfa4d3bf7f0555071b1b/net-zero-strategy-beis.pdf

2 https://ukhealthalliance.org/sustainable-healthcare/

3 https://juststopoil.org/2024/07/10/paint-the-town-orange-just-stop-oil-wins-first-demand/

4 https://unfccc.int/files/meetings/paris_nov_2015/application/pdf/paris_agreement_english_.pdf

5 https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM.pdf

6 https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/consumption-co2-per-capita

7 https://ourworldindata.org/carbon-footprint-flying

8 https://carbonindependent.org/carbonbudgets.php

9 https://cusp.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-29-Zero-Carbon-Sooner-update.pdf

10 https://carbonbudget.manchester.ac.uk/reports/

11 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(23)00174-2/fulltext